Continuous Monument

Superstudio, Tacita Dean, Lisa di Donato, Myeongsoo Kim & Andrew Ross

a digital exhibition

April 1st - May 15th, 2021

Individual Artworks

Install Views

Press Release

How do we relate to the landscape in our modern world? How do we locate ourselves in our physical environment when we often occupy an online space simultaneously? The exhibition Continuous Monument examines these two questions within a distinct group of artworks spanning five decades. The artists turn to their memory of a landscape and to their hopes for the future to look for answers. Ambitions for more perfect relationships with nature are tinged with their unavoidable dystopias and homogenization, each artist finds themselves looking back as much as forward.

Superstudio imagines an alternative future where global monoculture, in the form of the grid, is devouring the landscape. In its negative state (environmentally, culturally, spiritually) this grid is known as the Continuous Monument, from which the show acquires its name. When in its utopian version the grid is called Supersurface, a surface we can plug into and receive food, shelter, communications; anything we might need to live an anti-consumerist, nomadic life. A mode of living made possible only by a networked system.

In response to these two alternative visions of the future, the contemporary artists in the exhibition collect and document objects and images to try and hold onto the things that keeps us rooted in the natural landscape; details to locate themselves by. They search for the personal and the specific to fight the homogenization of the Continuous Monument.

“All the things I am attracted to are just about to disappear.” Tacita Dean (Guardian)

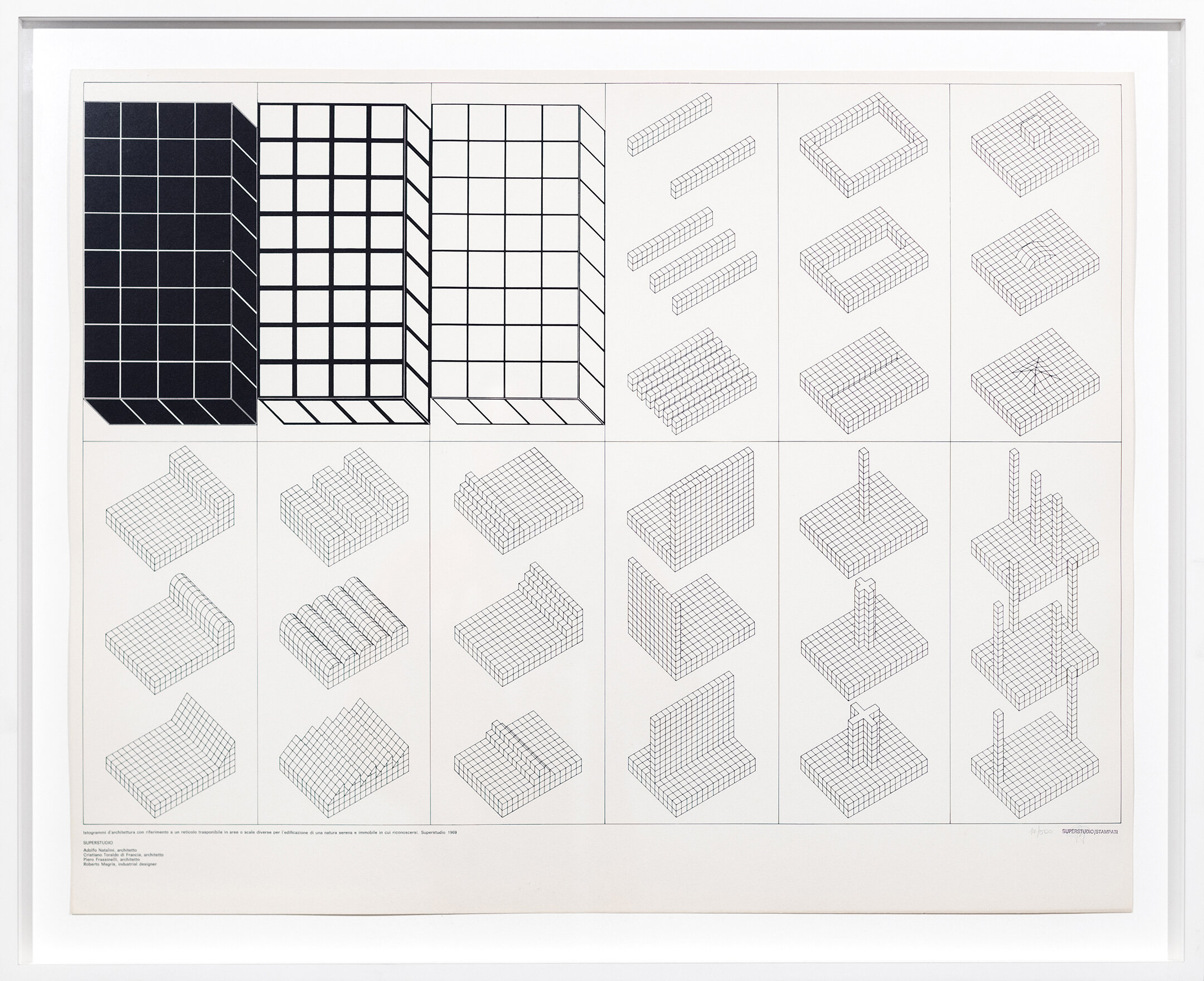

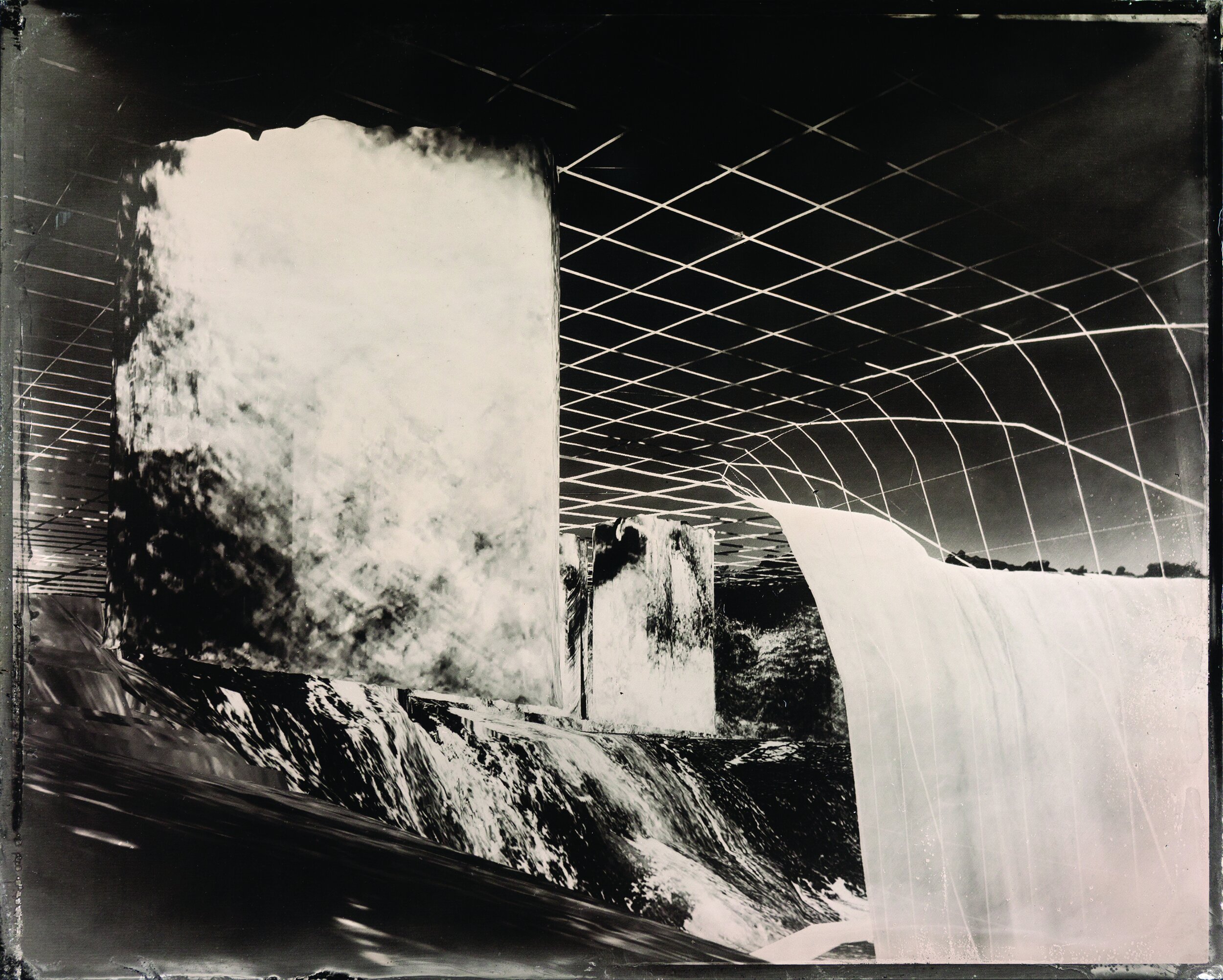

Superstudio was an architectural collective founded in 1966 in Florence, Italy. Considered part of the radical architecture and design movement of the late 1960s, Superstudio aimed to enact social change through architecture and to raise awareness of the harmful impact of construction on the natural environment. The project Continuous Monument, which a piece in this exhibition (Niagara o l'architettura riflessa, 1970) stems from, was a “single continuous environment, the world rendered uniform by technology, culture, and all the other inevitable forms of imperialism.” The second piece, Istogrammi di architettura, 1970, is part of the Histograms project. It diagrams a design system to be applied to all objects, furniture, environments and architecture, by means of a grid that is transposable to varying scales. A “behavioral scheme” or new mental process offering us a “total rethink of the typologies of classicism.”

Tacita Dean is a watcher of things (eclipses, shipwrecks, the passage of time). Her piece Fernsehturm, 2001, is a set of six color photogravures containing imagery taken from her 16mm film by the same name. Filmed on October 12th, 2001, the piece documents forty-four-minute static shot of the evening light changing across the interior of the rotating restaurant atop the Berlin Fernsehturm tower. Built between 1965 and 1969 in Alexanderplatz, Berlin, the tower was intended by the city’s Socialist Unity Party to be a monument to the future of the German Democratic Republic. She writes “The Fernsehturm has become the beacon on my Berlin horizon. I look out for it wherever I am… It was visionary in its concept and a symbol of the future, and yet it is out of date. The Fernsehturm embodies the perfect anachronism. The revolving sphere in Space still remains our best image of the future, and yet it is firmly locked in the past: in a period of division and dissatisfaction on Earth that led to the belief that Space was an attainable and better place.” (Quoted in Tacita Dean 2001, p.30.)

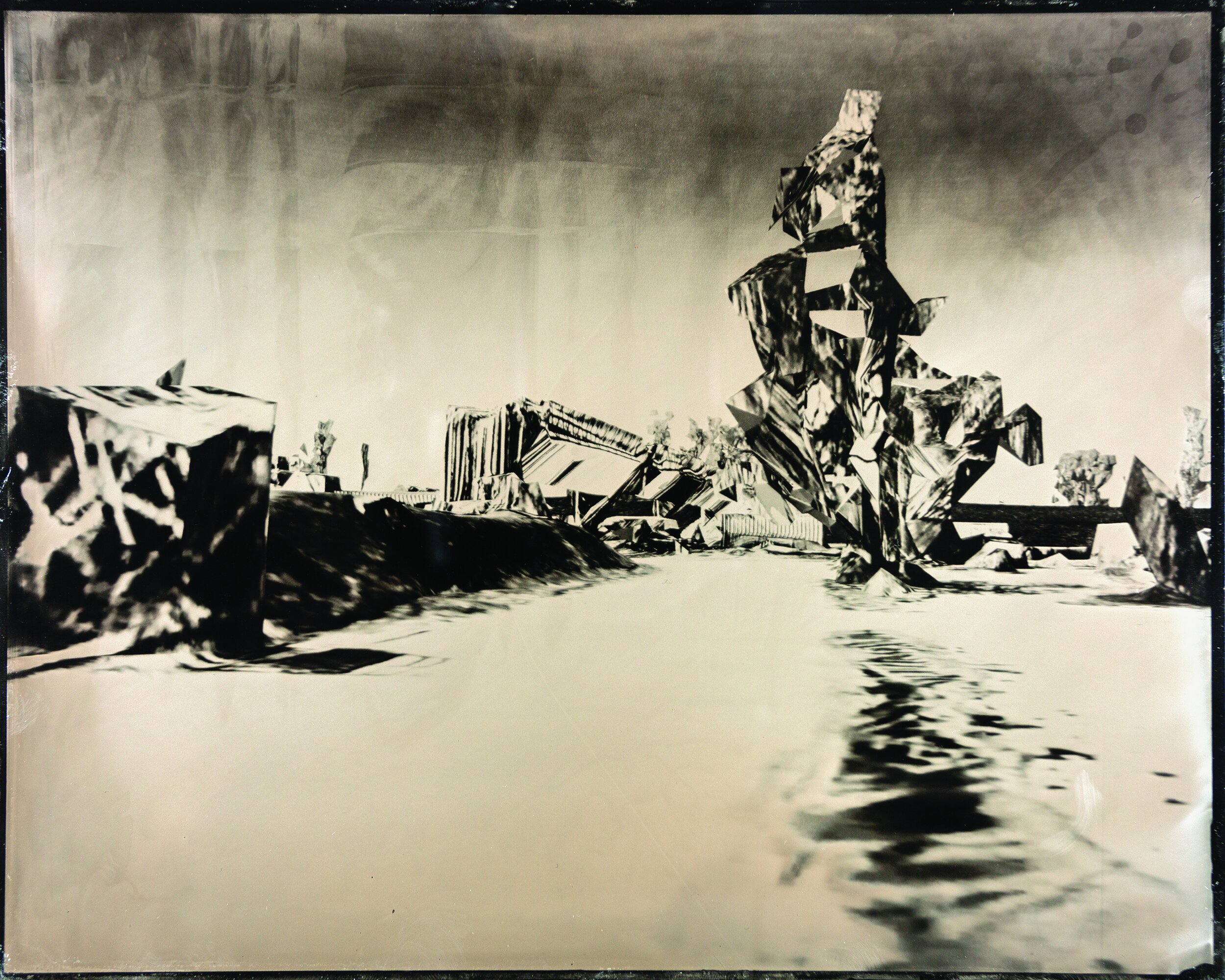

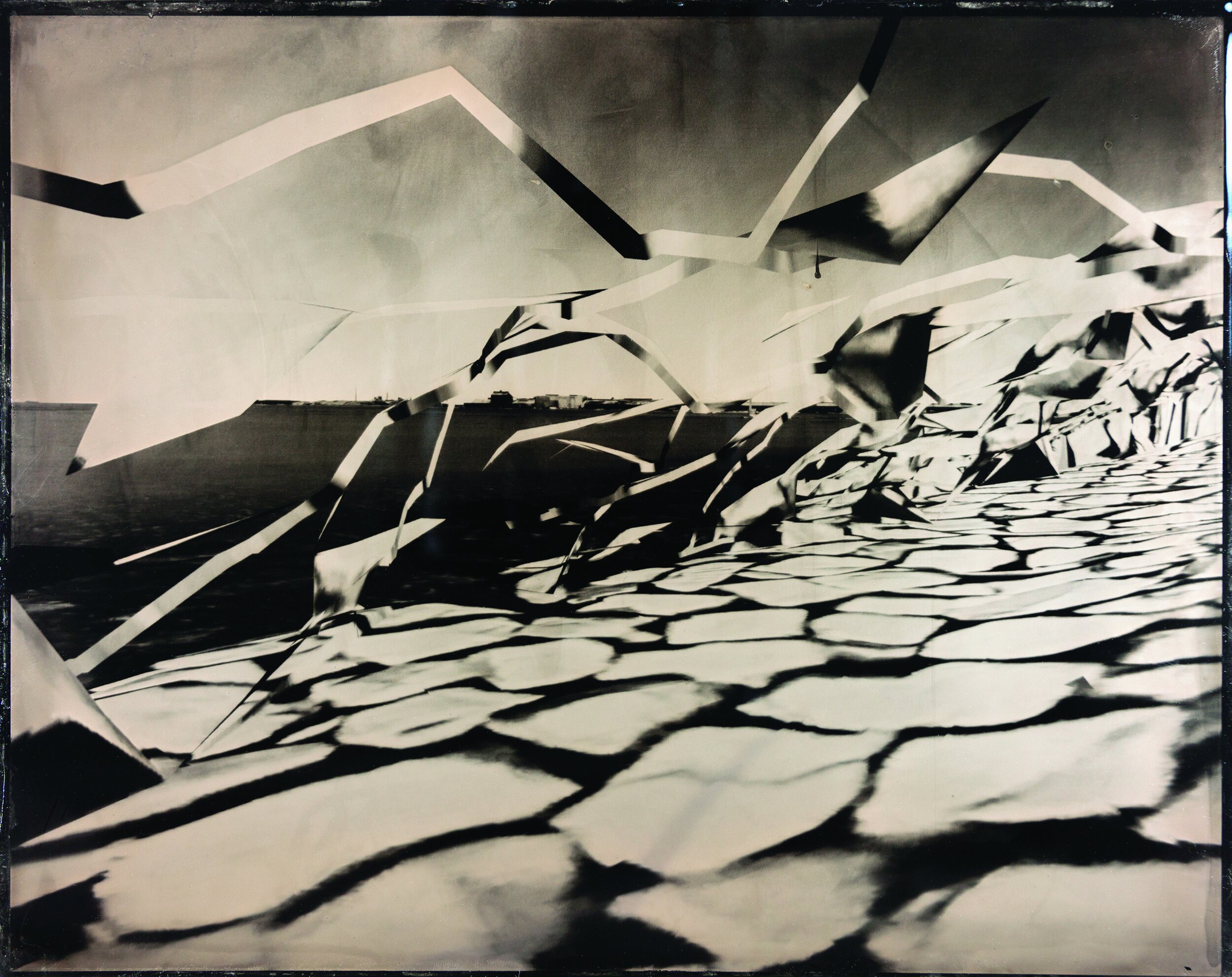

Lisa di Donato uses photography as medium, tool, and language to explore our modern perceptions of landscape. Her work combines two disparate technologies: the obsolete and antiquarian process of tintype, and new, mass-media imagery collected from Google Earth's 3D ground view. Through her computer screen, she visits places via Google such as industrial sites and remote natural spaces and collects screenshots to be translated into the tintype panels. Both processes trigger inherent irregularities, first in the digital projection of space generated by google algorithms and secondly in the photograph's physical chemistry during development. The resulting works represent a third reality to the one we stand in physically and the one we inhabit online, a landscape void of humanity. A rare space in the online world so entirely and continuously mapped and remapped. In this ecosystem “only traces of inhabitance appear in the intangible landscapes, as if the future had already been colonized and abandoned.”

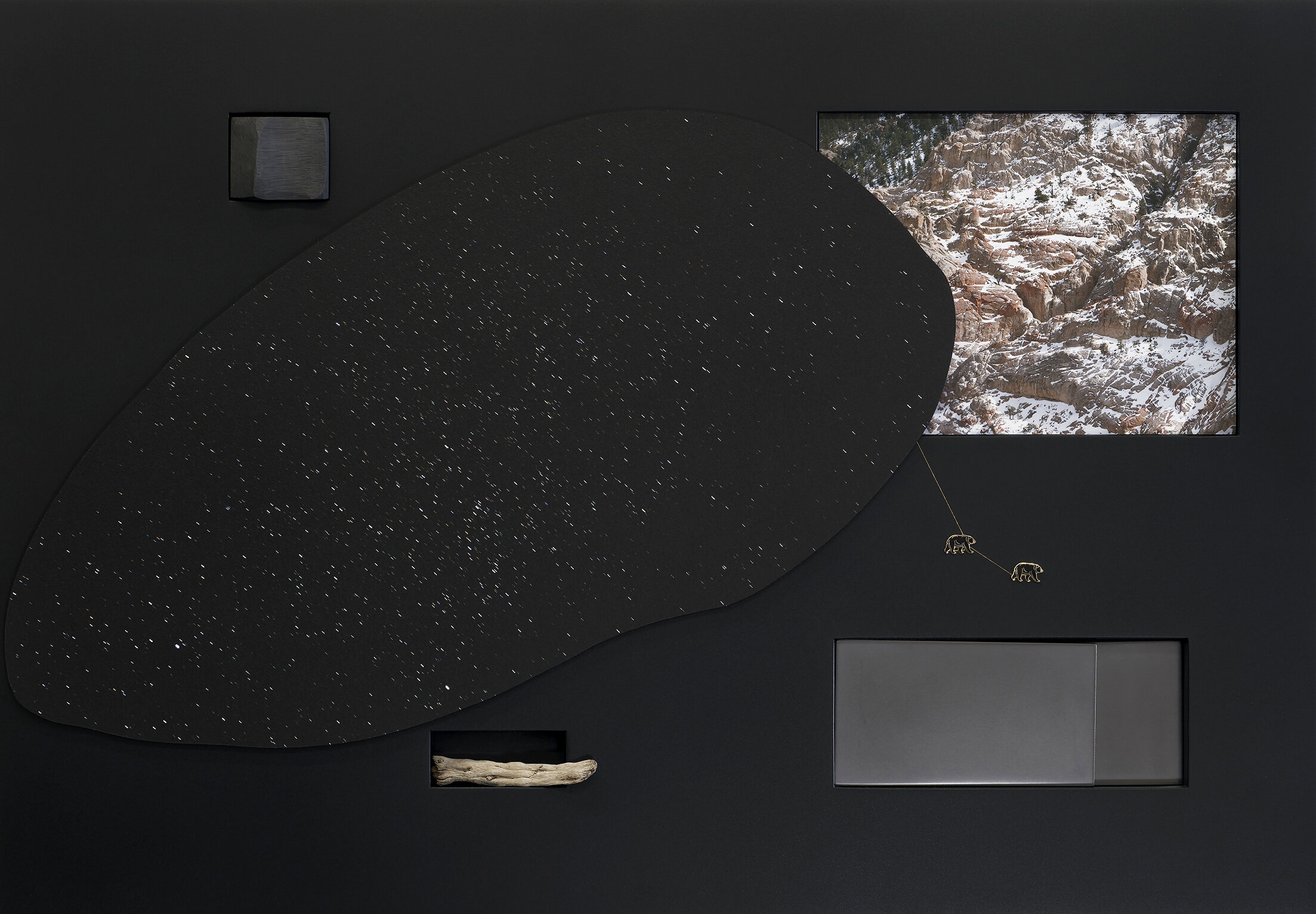

Myeongsoo Kim studied architecture before moving to the US from South Korea in 2002 but his landscapes, often of American west and Bolivian desert, are devoid of any traces of human occupancy. He chooses places with intangible or invisible traces of colonial or civic history - rock quarries, the Salton Sea, national park land - to document the landscape and collect small, seemingly irrelevant objects from the site. But all of these details are the physical relics of his memory and each artwork becomes a time capsule specific to the emotions and social-political histories surrounding a location. His careful use of materials and found objects turn each keepsake into a talisman, capable of transporting to us to specific coordinates in geological, celestial and personal time. But with all of the object cataloging and map-making within these artworks, the pieces are less about the specific destination and more about the inability to get there. There is a loss of accuracy with memory and Kim’s empty landscapes will not remain empty. He can never recreate a portal to the same place twice.

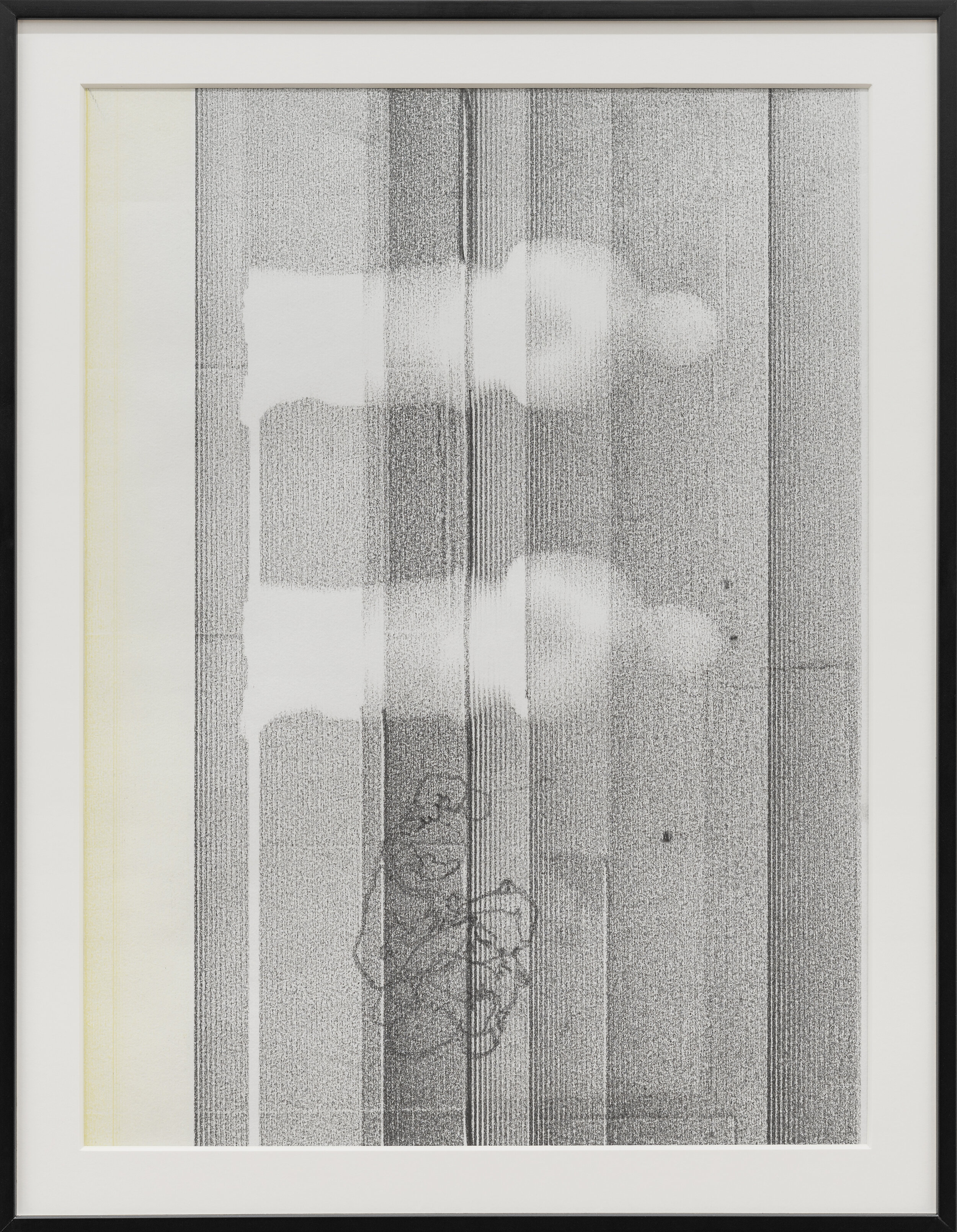

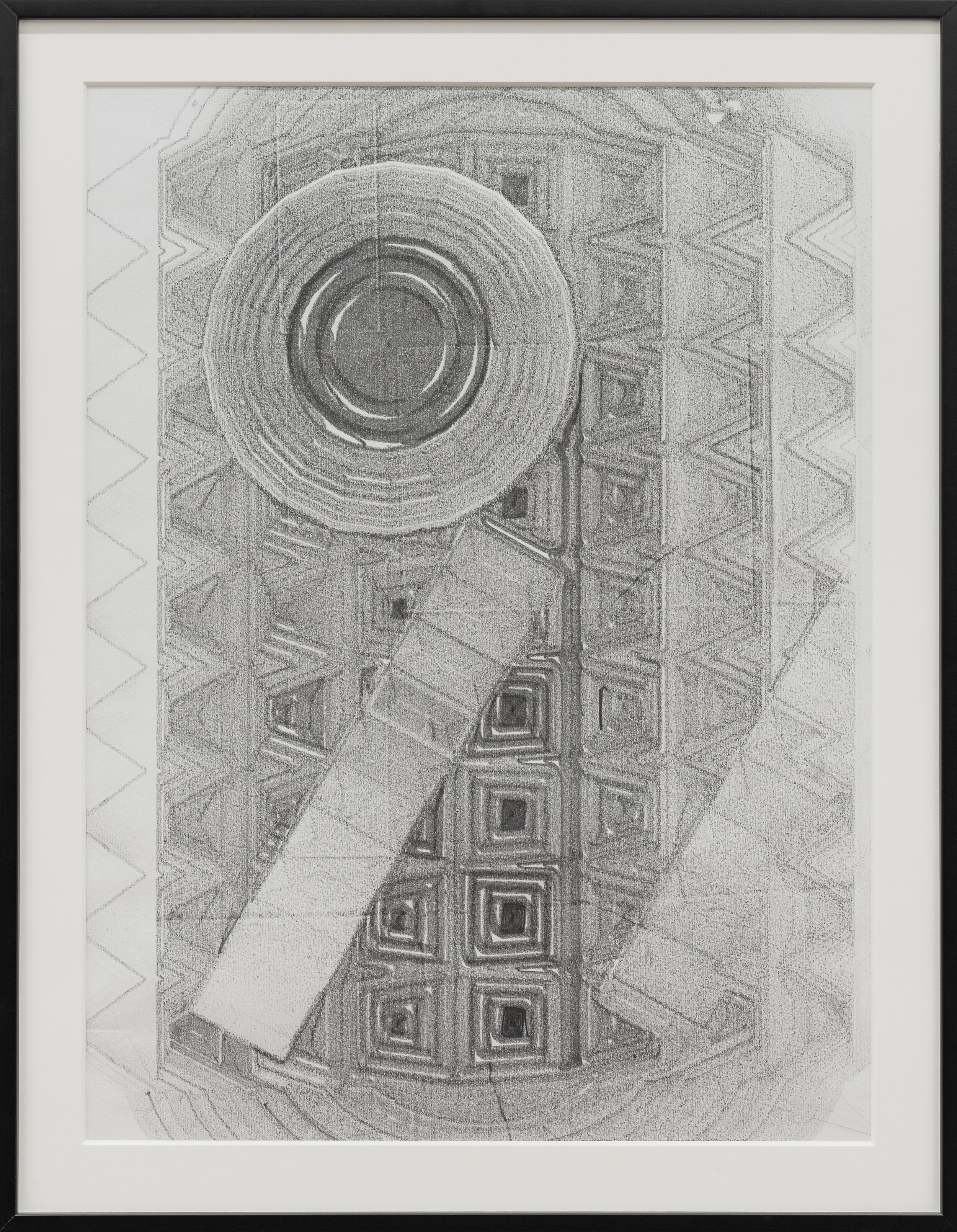

Andrew Ross’s three works are all primarily rendered using a CNC machine maneuvering a drawing implement within the xyz axis. The imagery shows 3D models from the inside out, as hollow structures or shells of their fully solidified files. T-shirts and brand decals emerge from the wireframe mist; social and cultural identifiers the artist sees as fluid. Interested in the product-streams of recycling old clothes and clothing as a false reference to membership into elite clubs such as sports teams and dojos, Ross isolates these markers and uses them to navigate the consumerist landscape. The piece “Blue Barrel Grinder,” 2019 references the practice of shipping barrels full of thrifted clothes to foreign countries, something that is especially common in the Caribbean. Much like the endless surface of Superstudio’s Supersurface, Ross pulls files from 3D modeled space to satisfy all of our needs. A form of hyper consumption that eradicates need, a nomadic life tainted with economic and geopolitical hierarchies.

Superstudio

Superstudio in 1970. Photo: The Toraldo di Francia Archive, Beinecke Library, Yale University.

Superstudio was an architectural firm founded in 1966 in Florence, Italy by Adolfo Natalini and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia (recent graduates of the Florence School of Architecture). It’s two original members were later joined by Gian Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro, Roberto Magris and Alessandro Poli.

Considered part of the radical architecture and design movement of the late 1960s, Superstudio aimed to enact social change through architecture and to raise awareness of the harmful impact of construction on the natural environment. Italy’s economy was still recovering from the Second World War and so opportunities for these young architecture students to see their designs built, or get an academic position at the university, were nonexistent. As a result, Superstudio never built any architectural structures. Instead, they produced an array of photocollages, short fiction, storyboard illustrations, prints, films and products that communicated their beliefs.

When asked to describe their work for a catalogue accompanying the 1973 exhibition Fragments From A Personal Museum at the Neue Galerie in Graz, Austria, Superstudio said, “In the beginning we designed objects for production; designs to be turned into wood and steel, glass and brick or plastic - then we produced neutral and usable designs, then finally negative utopias, forewarning images of the horrors which architecture was laying in store for us with its scientific methods for the perpetuation of existing models." These cautionary images often depicted an endless grid structure that would take over the world, a “single continuous environment, the world rendered uniform by technology, culture, and all the other inevitable forms of imperialism.” This structure is most iconic in Continuous Monument, a series of photomontages.

In 1967, the group established three categories of research: architecture of the monument, architecture of the image, and technomorphic architecture. Projects included Spaceship City where couples are born, made to reproduce while continually asleep in suspended animation and New York of Brains, a post-apocalyptic vision of the city as a giant cube on 81st Street comprising 10,000,456 human brains in liquid-filled containers. Superstudio disbanded as a collective in 1978, but its members continued to develop their ideas independently through their writings, via education, architectural practice and other design projects.

In 1972, Superstudio took part in the MoMA exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape and while still a collective, many of their projects were published in the magazine Casabella. There has been a resurgence of interest in Superstudio’s work including exhibitions such as Superstudio: Life Without Objects, at London’s Design Museum traveling to Pratt Manhattan Gallery/Storefront for Art and Architecture/Artists Space, (2003); Environments & Counter Environments at Chicago’s Graham Foundation (2013); Superstudio. The Secret Life of the Continuous Monument at the Venice Biennale (2014); and Superstudio 50 at Rome’s MAXXI (2016). Superstudio’s work can be found in the collections of several international museums, such as the Museum of Modern Art (New York), Israel Museum (Jerusalem), Deutsches Architekturmuseum (Frankfurt), Centre Pompidou (Paris), and MAXXI (Rome). The Natalini archive is held at the Beinecke Library at Yale University, New Haven.