Gracelee Lawrence: Marisol

September 8 – October 22, 2022

opening Thursday, September 8th

Artworks

Install Views

Press Release

Heroes Gallery is pleased to present new work by artist Gracelee Lawrence in conversation with María Sol Escobar (Marisol). Lawrence has long been inspired by Marisol’s haunting portraiture, humorous figuration and approachable social commentary and views Marisol to have considerable influence on her practice.

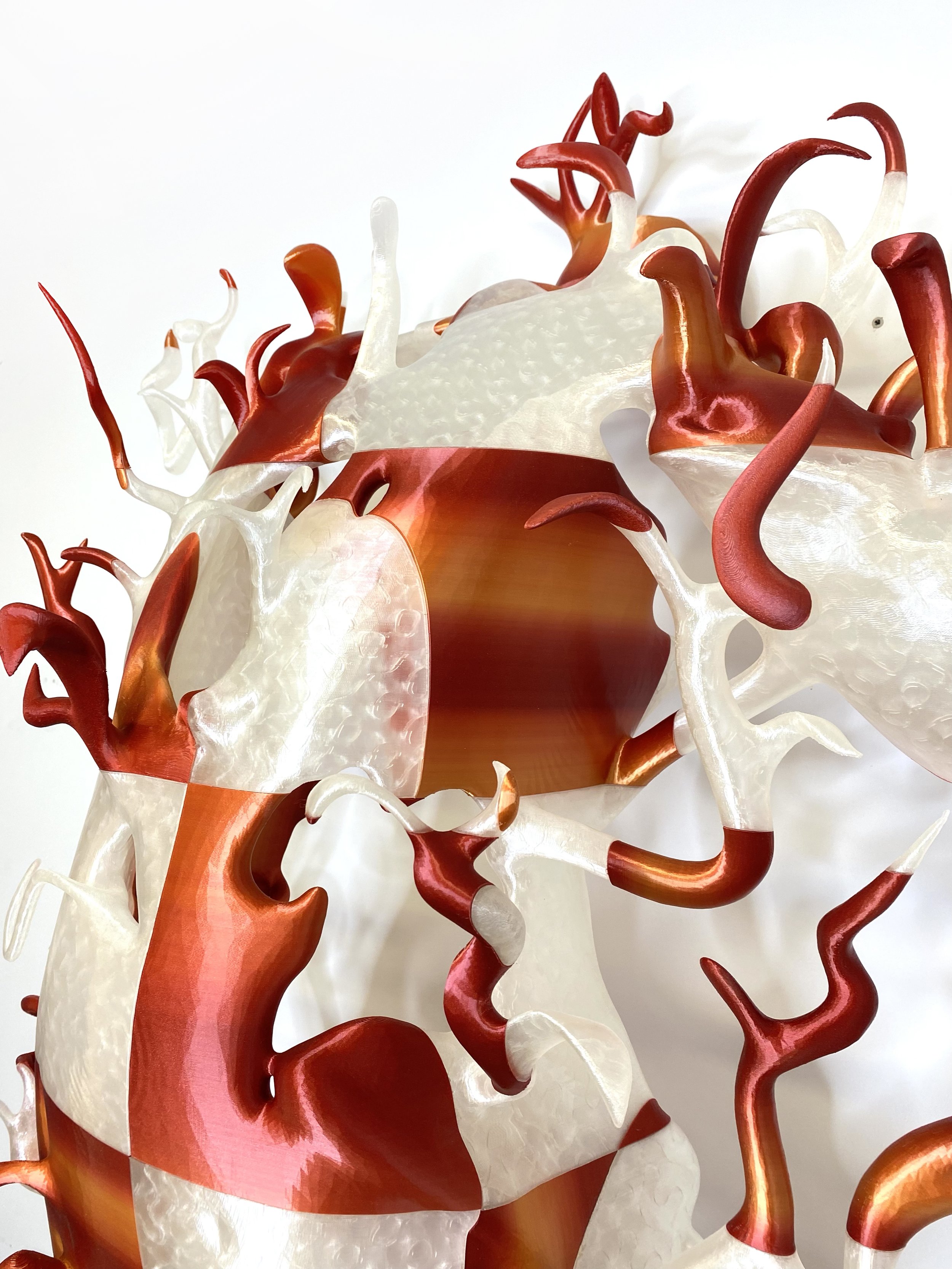

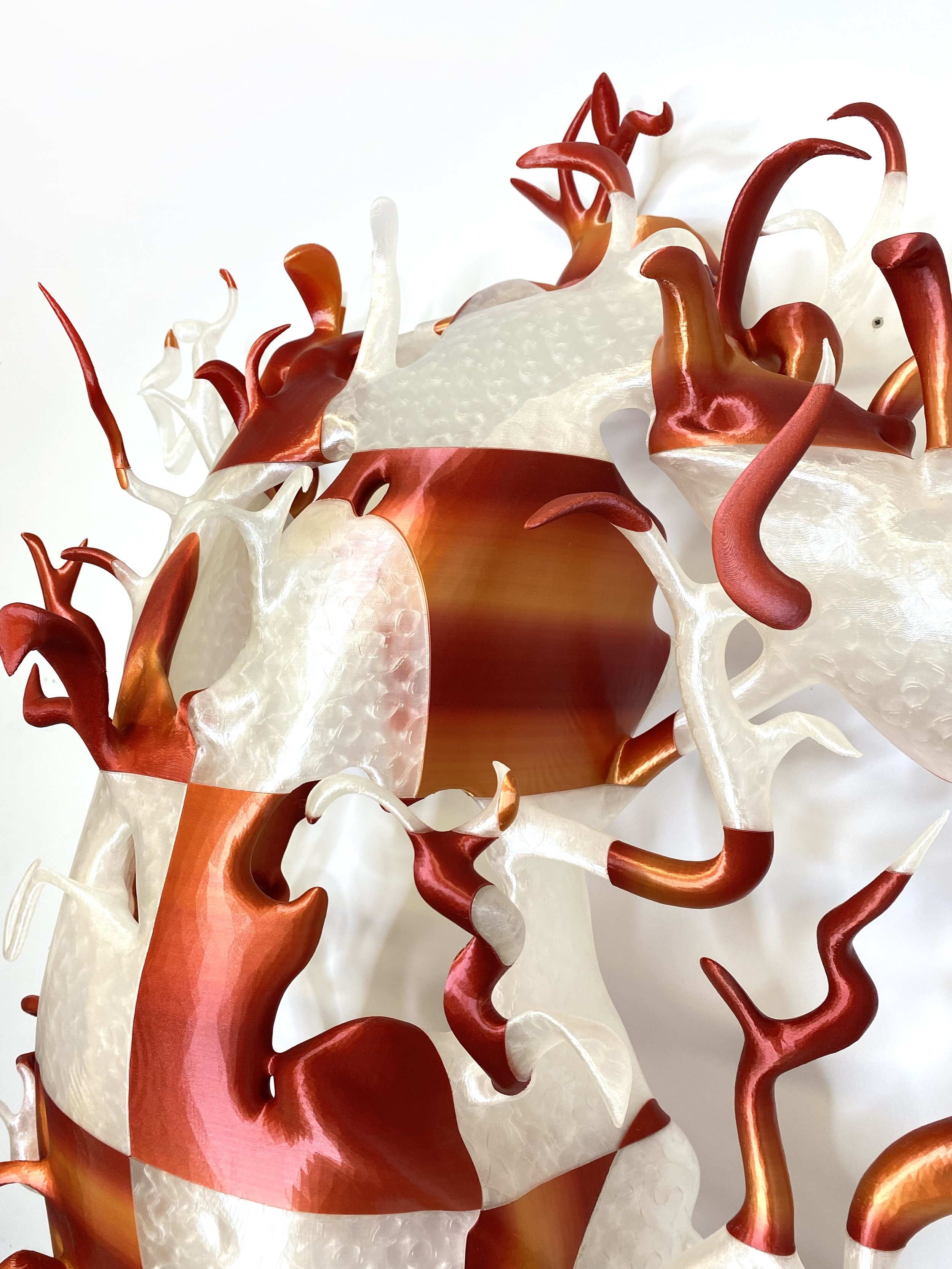

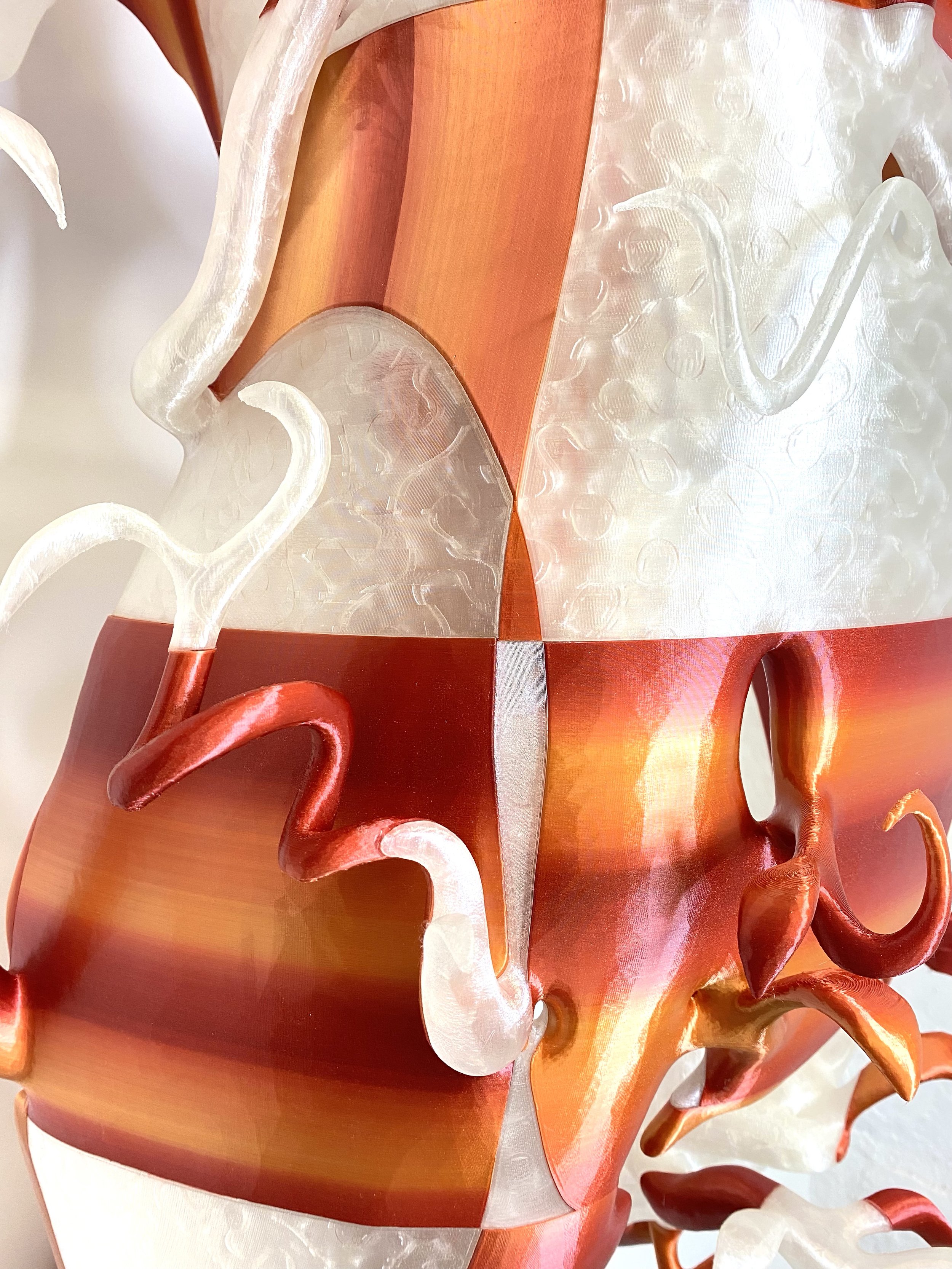

Gracelee Lawrence’s sculptures address the complex relationships between food, the body and technology. She takes 3D scans of herself and through a process of digital manipulation, hybridization and fragmentation, creates 3D-printed objects fabricated with polylactic acid (PLA) filament, a vegetable derived bioplastic. Her glossy creations are born of self-portraiture mutated into hybrid vegetable forms. The recognizable foods and organic flames interwoven with the artist’s body instantly speak to gendered consumption, sustenance, sexuality and humor while their technological production hints at bio-cyborgism and parallel, occasionally macabre, digital realities.

In his 1964 New York Times review of Marisol’s show “Marisol: The Enigma of the Self Image,” Brian O’Doherty states that Marisol “refuses to join you in the contemplation of her own image, but remains an island, sometimes distant, sometimes close, according to the conventional weather. But always separate.” Best known for her totemic carved figures and loosely associated with the Pop movement of the 1960s, Marisol often used plaster casts of her face and hands or photographs of herself in her sculptures. Viewing them not as traditional self-portraits, but as possible identities, she used her sculptural avatars to explore sexuality and the roles available to and forced upon women. In this manner, both Marisol and Lawrence are remaking themselves over and over again; using their likeness not to explore the inner self, but to represent societal expectations, gender norms and alternative futures.

In addition to her own likeness, Marisol used recognizable imagery in her work to make sure it was universally understood outside the rarified art world. Lawrence also prioritizes the accessibility of her works, choosing foods because it’s sensorially understood as an object and material across all humanity regardless of one’s background. Fruit and vegetables are often used to communicate the growth of a cancerous tumor or the size of a baby as it is developing, their relationship to our bodies going beyond the immediate nutritional level. A still life of produce has historically been used as a metaphor for desire, mortality, fertility and abundance, displaying wealth and materiality through culturally encoded language. Their use as a representation of decay and impermanence is also intertwined with fruit and vegetables’ politicization via colonialism and global capitalism. To trace a corn cob or pineapple from seed-to-plate draws a path through the maze of government subsidies, economics and sociopolitical access.

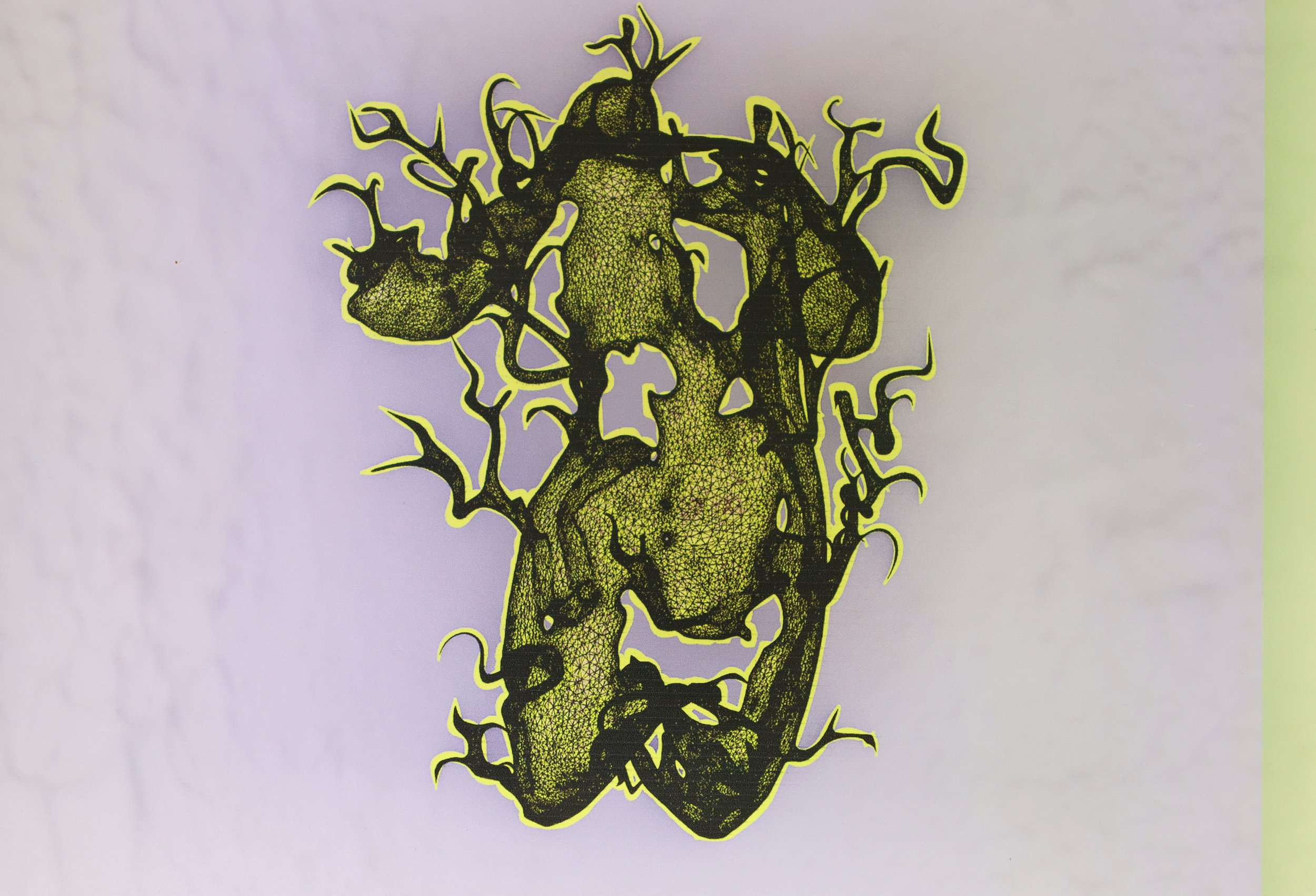

Lawrence tackles this language of food and identity within the digital space. Although the works in the gallery are physical objects, they are saturated with the residue of digital manipulation from the process of their production. What does it mean to be an organic, physical body—whether human, vegetable, or animal—in digital space? As barriers between "virtual" and "real" spaces continue to dissolve, how do our bodies exist when the possibilities of augmentation are endless? Lawrence’s sculptures are broken apart into checkerboard squares and reassembled into enlarged totems, intermingling dread for our loss of self and colorful techno-optimism for what the nonbinary future may hold. Marisol’s lithographs similarly play with the fragmentation of the body’s boundaries. Their outlines are blurred with scratched, hashed lines and penetrated with disembodied hands, resulting in the same conflict; are we dissolving into a more-perfect collective whole or are the walls of our identity being overrun?

Gracelee Lawrence earned her MFA from University of Texas, Austin (2016) and her BFA from Guilford College (2011). Her recent solo show at Postmasters (2022) was her second in New York after Thierry Goldberg Gallery (2019), and the final show in the gallery’s Tribeca location. Past group exhibitions include Marinaro Gallery (New York, NY), Atlanta Contemporary (Atlanta, GA), Kavi Gupta Gallery (Chicago, IL), and more. She has installed large-scale outdoor sculptures at the Wave Hill (Bronx, NY), Museum of Museums (Seattle, WA), Franconia Sculpture Park (Shafer, MN), Mary Sky (Hancock, VT), among others. Her work has been reviewed extensively, including in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Hyperallergic, Artnet News, and MAAKE Magazine. She is currently an Assistant Professor of Sculpture at the University at Albany, SUNY and a member of the artist collective Material Girls, a group that builds community through collaboration and material knowledge.

Marisol in her studio, 1993. Photo: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, © Nancy Lee Katz, [reproduction number, e.g., LC-DIG-ppmsca-12345].

Marisol (1930–2016) was born María Sol Escobar in Paris to Venezuelan parents. She moved to Venezuela in 1935, followed by a move to Los Angeles in 1946 where she studied art at the Otis Art Institute and the Jepson Art Institute. After a brief stint at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, she finally arrived in New York to take classes at Art Students League, Hans Hofmann’s studio, the New School for Social Research and the Brooklyn Museum Art School.

Although initially influenced by the prevailing school of Abstract Expressionism, Marisol attributes the shift towards her sculptural style to seeing pre-Columbian art in Mexico while visiting her father and in a New York gallery show in the early 1950s. Her reaction was to make totemic figures; assemblages of carved wood, painting and found objects. Because her figures were satirical in nature and highly accessible to the viewer, she was often associated with the newly emerging Pop Movement. However, the work often escaped definition, existing between movements while forging a pioneering feminist trajectory.

Following a group and solo exhibition at Leo Castelli’s gallery in 1957, Marisol grew in popularity with highly attended shows at Stable Gallery, Sidney Janis Gallery and glossy Life Magazine articles. She became associated with Andy Warhol’s factory, where in 1964 she was cast in two iconic Warhol films; Kiss and The 13 Most Beautiful Women. In 1968, she represented Venezuela at the Venice Biennale and was included in Documenta exhibition in Kassel, Germany.

By the 1970s and 1980, Marisol was traveling heavily between New York, Caracas and various European cities. She began experimenting with printmaking, drawing, photography and resin casting, taking on commissioned portraiture and set/costume design. Unfortunately, her work fell out of fashion as was not exhibited outside a few circles during this time.

Upon her death in 2016, Marisol bequeathed her estate to the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (now the Buffalo AKG Art Museum). Works by Marisol are included in the collections of many major museums, including those of the the Art Institute of Chicago; The Metropolitan Museum of Art; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Smithsonian Museum of American Art; and the Whitney Museum of American Art. A major retrospective exhibition organized in 2014 by the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, “Marisol: Sculptures and Works on Paper,” subsequently traveled to El Museo del Barrio in New York.